Independent Photographers in an Age of Few Women Owned Businesses.

WLP Story Number 1 ~ by Margaret Riddle

Iowa – born Alice and Clara Rigby arrived in Everett, Washington at the dawning of the 20th century and did what few other women of their time dared to try: they owned and operated a professional photo studio. From 1905 to 1915, the Rigby and Rigby Photo Shop successfully competed with prominent local photographers J. D. Myers and Bert Brush, as well as half a dozen smaller firms, and found a niche for themselves in a profession dominated by men.

The Rigby sisters were part of a growing number of women in the early 1900s who sought social and economic independence, and the West was fertile territory for this progressive kind of thinking. Issues of the day included the rights of working women and, more significantly, a woman’s right to vote. By 1910 Washington State would grant women suffrage.

But the need for independence had more immediate and personal roots for Alice and Clara. As the result of an unhappy marriage, their mother, Delia, encouraged her daughters to seek professions, not husbands. And, in like manner, Delia’s sister, Emma Sarepta Yule, was a highly successful and independent lady. Arriving at the Everett town site in 1891, Emma Yule became Everett’s first school teacher. When other teachers were hired, Emma became Principal. From 1897 to 1900, she served as Everett’s Superintendent of Schools. In 1900, Emma Yule left Everett to teach in Alaska. Showing such independence, intelligence and ability, Emma was likely a significant role model for her young nieces.

The Rigby sisters chose professions that were considered acceptable for women of their time. Alice became a teacher, and Clara pursued photography. In Washington State, female teachers could not be married, a requirement that continued until after World War II. And photography was, as the Kodak Company advertised at the turn of the century, an appropriate occupation for women. It was considered a proper artistic endeavor, and work could be done in or near the home. Photography studios routinely employed women in this area, although most worked as silent partners in the darkroom or as retouchers, their identities invisible behind a male studio name.

Rigby family stories recall that Delia came to Everett with daughters Clara and Alice at the turn of the century, but city directories indicate otherwise. Alice seems to have come to Everett first, arriving alone in 1900. She is listed that year as teaching at Lincoln School, in the elementary grades, and living with Aunt Emma Yule at Everett’s elegant Monte Cristo Hotel. That year, however, Ms.Yule became involved in a dispute with the school district over her pay and departed to teach in Alaska.

Clara began her career working as a retoucher in 1892 for the J. C. Wilson Studios in Cherokee, Iowa, moving next to Colorado where she did similar work for various studios. In 1904, she and her mother came to Everett. Photographer Loren Seely hired Clara as his retoucher. One year later, she bought the Seely studio, acquiring both his studio location and negative collection. Alice quit teaching to work with Clara, and for nearly ten years, the Rigby sisters operated the business with considerable success.

Rigby family members say that the sisters called their studio Rigby and Rigby in an attempt to conceal the fact that they were women, but Clara and Alice also found ways to capitalize on the pluses of their gender. The Rigbys advertised as “Portraitists” who specialized in baby pictures, and it can be imagined that Alice drew on her teaching experience to aid in photographing the young.

By 1900, times were changing economically for the region. With the severe depression years of the 1890s now in its past, the Pacific Northwest was once again feeling prosperous and optimistic, and Everett gained its share of new arrivals, many of them immigrants, seeking to better their lives in a new place. In the century’s first decade, Everett’s population tripled.

Everett now had families, and families had “Kodaks”. By 1900, photographic advances and cheaper prices made it possible for amateurs to take their own pictures. Working with either a small glass-plate camera or a new popular roll film model known as the postcard Kodak 3A, they photographed their families, their homes and businesses, as well as activities on their city streets. They also recorded heavy snowfalls and floods and documented their vacations and trips abroad.

Often poor exposed and usually of poor composition, these photographs were, nevertheless, priceless ways of sharing experiences with family and friends miles away. Studios processed and duplicated these amateur views, often printing them as postcards, which could be mailed. Over the years, these amateur postcard images have become historical treasures because they often documented events of everyday life in a way that studio views do not.

Film processing offered steady work, and the Rigbys gained their share of this business. However more money was being made in portraiture and commercial photography. Professional portraits were highly prized. Photographed with balanced lighting, set against a studio background and retouched to make its subjects look their best, the professional portrait was considered a work of art, and professional photographers were held in high regard. Competition was keen, and to prosper in the work, a practitioner needed to be good at business as well as art. The Rigby sisters skillfully balanced both and survived in competition with other excellent photographers. The Rigbys even opened additional studios in Monroe, Snohomish and Arlington, and commuted by train between towns.

In 1913 they temporarily closed their studios to visit Japan. Scrapbooks assembled by the sisters document their trip. Upon returning to Everett, the Rigbys relocated their studio at 2802 Colby. But the joyful years were behind them. Alice soon was diagnosed with cancer and died at 44 years of age. Clara continued the business for only a few months after Alice’s death, then closed the studio for good.

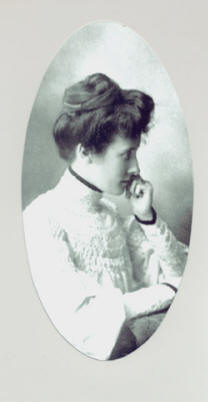

Above: Alice Rigby

The Rigby negatives were stored for many years and then dispersed, some finding their way into the files of Lee Juleen, which are now housed at the Everett Public Library. Few of their photos remain. Only a small number of negatives and postcards in the Everett Public Library are easily attributed to them. What the Rigby family has retained are priceless photos that Clara and Alice took of each other, showing the fine quality of their portraiture.

In the 1920s Clara married James Casperson, an employee of the Everett Pulp and Paper Company. The couple moved to California where they grew and marketed nuts. Clara eventually returned to live in Everett. She died August 27, 1953.

Rigby descendants speak of Alice as the quieter and gentler sister, but while Clara was a stern and imposing figure to her relatives, it is Clara they remember, since she lived long enough to be a presence in their lives. What made the sisters different from other Snohomish County women working in photography at that time? Were the Rigbys wealthy enough to be able to buy a photo studio while the average retoucher was not? “No,” the family says, “they didn’t have money.” Perhaps just the skill, the drive and the dream. And that, the sisters certainly had.

Sources: Donald Rigby, an oral history interview circa 1980 by Margaret Riddle and David Dilgard;

Iris Broad, an oral history interview, August 20, 2001, by Margaret Riddle;

Polk’s city directories for Everett; Washington, 1900 to 1915. © 2006 Margaret Riddle;

Previously Published in Snohomish County: An Illustrated History

Kelcema Press, 2005.