~ She has her day in court

By Betty Lou Gaeng

Anastasia had freckles! Her skin color was light! As a young woman, she married a well-known and prosperous white man from Scotland—Alexander Spithill. Dr. Charles Buchanan, a representative of the United States Government, decided that Anastasia was foreign and did not belong on the Tulalip Indian Reservation. Nor, according to Dr. Buchanan, was she entitled to the land allotted to her and her children in 1886. Even though the family had built a road and homes, and planted gardens and orchards on the property, he informed Anastasia it was not her land.

Anastasia was born about 1853 at Skagit Head on Whidbey Island. When she was two years old her full-blood Indian mother died, and her white father was long gone. Anastasia lived with her maternal grandfather Sadkok, or Wonnapot, as the Indians called him. To the white people he was known as Chief Napoleon Bonaparte of the Snohomish. Chief Bonaparte became one of the last survivors of the signers of the 1855 Point Elliot Treaty. The widowed Bonaparte and little Anastasia went to live on the newly designated Tulalip Indian Reservation. There, and at places her grandfather traveled, Anastasia was at his side or playing with other Indian children close by.

Anastasia was noticed, not only because she was always in the company of Chief Bonaparte, but because her little white face was covered with freckles. People wondered why this white child was always with the Indian people. Other Indians did not question Anastasia’s identity—they had always known she was one of them. She even had a special name—they called her Popstead, meaning Little Boston. The well-known Tyee Peter was her uncle.

Indications are that Anastasia was a very precocious child, and grew to be a woman with the same tendency. Not hard to believe as her grandfather, an important man with the Snohomish, was noted for his dignified air of superiority, and the red coat he wore. His attitude and appearance did not always endear him to the white men who had to deal with him. No doubt, little Popstead being in the company of her grandfather much of the time, adopted this same air of superiority, and her appearance was noteworthy.

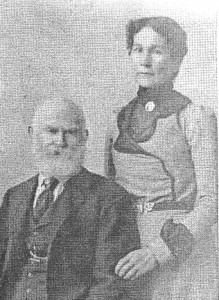

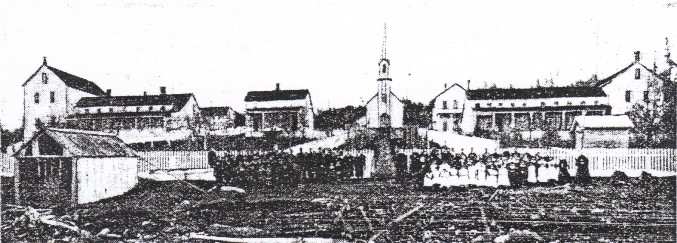

Anastasia stayed with her Grandfather Bonaparte until she was 13 years old. She was then sent to Mission Beach on the Tulalip Reservation to attend Our Lady of Seven Dolors Indian Mission School conducted by the Sisters of Charity of Providence at St. Anne’s Catholic Mission. She attended the school until she left to marry an older man, the widowed Alexander Spithill. She became stepmother to his two young sons, Neil, age seven, and Duncan, age four. Mary, their mother, had been a full-blood Stillaguamish woman. Alexander and Anastasia were married February 27, 1870 at St. Anne’s Mission by Father Eugene Casimir Chirouse, O.M.I. Writing in French, Father Chirouse recorded this information, noting that Anastasia’s mother was a Snohomish Indian.

Nine children were born to Anastasia and Alexander. Eight would survive: Matthew, May, Alexander Jr., John, Cecilia, Inez, Zella and David. Neil and Duncan grew up knowing only Anastasia as their mother. In fact, Duncan must have developed a personality much like his stepmother. Father Chirouse writing in his diary in the winter of 1875 made the unusual statement “Mrs. Spithill and Donkan come to confession and behave well.”

The family first lived on the reservation at Mission Beach where Father Chirouse employed Alexander as carpenter. They then moved to Mukilteo and later Marysville. When Anastasia received an allotment, the family maintained dual residences. The first requirement on the allotment land was to build a road to make the property accessible. When this was done, a home was built and furnished. Land was cleared and gardens and an orchard planted. As the children grew, more land was cleared and homes built for them.

There had been early controversy in the agency as to whether Anastasia and her children were entitled to allotments. In 1886, the Acting Commissioner of the Department of the Interior, Office of Indian Affairs, A. B. Upshaw, notified the then Indian Agent Patrick Buckley that even though Anastasia had a white husband, she and the children were entitled to allotments.

Years later, Dr. Buchanan chose to ignore this ruling. In 1901 when Dr. Buchanan was appointed Superintendent and agent of the Tulalip Indian Agency, he was not convinced that Indian women married to white men were entitled to allotment land. He also demonstrated hostility toward the Spithill family and began a crusade, including warning them to vacate the property. He then awarded a portion of Anastasia’s land to William McLean, a man of Skagit and white blood. This began a seven-year dispute, ending only when settled by the courts.

On May 26, 1904, Anastasia filed a complaint in the Ninth Circuit Court of the United States (in Equity) against William McLean and Dr. Buchanan in his capacity as a representative of the U.S. Government. Later the United States was also included as a defendant. On March 4, 1908, after a very lengthy and bitter hearing before Eben Smith, Master in Chancery, with testimony by many witnesses, the court issued its decree stating that William McLean’s allotment was cancelled and he was “perpetually restrained and enjoined from asserting any claim whatever.” The court also stated that “Charles M. Buchanan, as Superintendent and acting Agent of the Tulalip Indian Reservation and his successors in office be and they hereby are forever restrained and enjoined from interfering with the complainant’s occupation and possession of the lands herein described.”

Little Popstead had won her lawsuit. The Heirship Ledger of the Tulalip Indian Agency records the land patent dated September 24, 1909 on behalf of Anastasia and her children, with the exception of her youngest son David who died May 19, 1908 at the age of 20. No portion was awarded to Neil and Duncan since they were not of Anastasia’s blood.

Anastasia Spithill, became a widow in 1920 when Alexander died at the age of 95. Anastasia lived another 12 years—her death occurring in Portland, Oregon on January 14, 1932.

Sources:

Anastasia Spithill, et al., Plaintiffs v. William McLean, Charles M. Buchanan, as Superintendent and acting agent of the Tulalip Indian Agency, and the United States, Defendants. Case File No. 1194, The Circuit Court of the United States for the Western District of Washington, Northern Division, Ninth Circuit (1904). Record located at NARA, Seattle Office, RG21, U.S. Circuit Court, Seattle; Civil and Criminal Case Files.

Ancestry.com Oregon Death Index, 1903-98 [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: The Generations Network, Inc. 2000. Original data: State of Oregon, Oregon Death Index 1903-1998. Salem, OR, USA: Oregon State Archives and Records Center.

Diary of Rev. Father Eugene Casimir Chirouse, O.M.I., September 1875 – April 1876. St. Anne’s Catholic Mission, Tulalip Indian Reservation, Washington Territory, USA. Translated from the French language.

© 2008 Betty Lou Gaeng, All Rights Reserved; WLP Story # 57