She Stopped the Bicentennial Wagon Train And Made Sure Her People Were Recognized

By Ann Duecy Norman

“…people are not accustomed to thinking of Native women as feminists, leaders, and contributors to social change. Their songs are unsung” ~LaDonna Harris, President and Founder, Americans for Indian Opportunity

As a young child, Esther Ross often listened to family stories. Her father, Christian Johnson, liked to talk about his noble Norwegian ancestors, but her favorites were tales told by her mother, Angelina, about Esther’s great grand-father, Chief Chaddeus, and how Angelina’s people, the Stillaguamish, had been driven from their lands.

Esther was born in 1904 in Oakland, California, and spent her childhood there. She was intelligent and lively and had lots of friends. It was not until she was in high school that her classmates learned of her Indian heritage. Then, suddenly, to her surprise, she was taunted about her ancestry and, worse yet, people she thought were her friends shunned her. She turned to her native family for support and, to her dismay, learned the government had declared that the Stillaguamish people were no longer an official tribe.

After completing high school in California, she continued her education, supporting herself with jobs ranging from secretary to newspaper reporter. In 1926, she was contacted by relatives in Washington State who asked her to come to Washington to help organize the Stillaguamish in order to file claims against the federal government. Esther packed up her belongings and her new baby, and she and her husband headed north.

When she arrived in Arlington, she immediately began reading pertinent documents and interviewing tribal elders. She learned that for millennia, her people, like those of many Puget Sound tribes, had lived in small bands that came together seasonally or for mutual assistance in times of trouble. Their villages had been scattered along the many branches of a river that wends its way through what is now northern Snohomish County. Their primary mode of travel was canoe; their major source of protein was salmon; and the focal point of their culture was their river homeland, as reflected by the tribe’s anglicized name, “Stillaguamish” which translates as “people of the river”. [For more discussion of the complex Lushootseed language , see below]

In the mid 1800’s, to make land available for white settlers, the United States government had ordained that all Indians be removed from their lands, taken to reservations and turned into farmers. In 1855, having negotiated agreements with the various tribes of northern Puget Sound, the major concession being that the Indians be allowed to continue to fish in their “usual and accustomed grounds,” the governor of Washington Territory, Isaac Stevens, called together tribal representatives, among them the Stillaguamish. Their representative signed what came to be known as the Point Elliott treaty, a document written in a language he and his people did not understand and with implications that were not made clear to them.

According to oral tradition, the Stillaguamish had believed that as a result of their cooperation and assistance to white settlers, they would be given their own reservation. When they learned they had to leave their valley and go to the Tulalip reservation, most of them quietly disappeared into the forest. Perhaps, because of their small numbers, tribal members were not actively pursued by federal authorities. Some found work as loggers or fishermen. Some, like Esther’s grandmother and mother, married non-natives. Others cleared land for white farmers in places that had, for innumerable generations, been Stillaguamish ancestral homes.

Esther also learned that the federal government did not officially recognize landless tribes, and for that reason, the Stillaguamish and their descendants were unable to obtain the benefits promised by the Point Elliott treaty. In July 1926, she convened a tribal meeting at the Arlington City Hall. Officers were elected, and a representative of the Northwestern Federation of American Indians provided information about filing claims against the government. In less than a month, with Esther’s help, the tribe’s sixty-six officially enrolled members had filed claims, both for land losses and for failure to pay the treaty’s specified annual appropriation for the preceding twenty-five years.

For nearly fifty years, Esther volunteered her time with other Tribal members. They held meetings, kept minutes, conducted research; she read and interpreted legal communications for tribal members and communicated with government officials. During all those years, she heard a lot of promises which were never honored.

During this long discouraging process for the Tribe, she became so tenacious that elected officials were known to duck out of sight when they heard she was in the building, and she was renowned for embarrassing government officials with her keen knack for making her point. Despite her continued efforts, by 1975, the tribe and its members had yet to be recognized or recompensed.

That summer, an unusual opportunity presented itself. The Bicentennial wagon train was making a trip across the continent, and according to the Everett Herald, was scheduled to pass through Island Crossing located “just an arrow’s flight away from the combination office and souvenir store” that served as Stillaguamish headquarters.

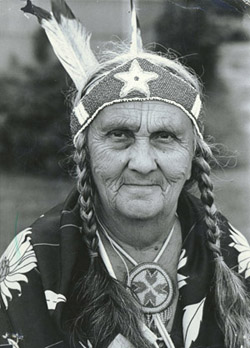

Esther Ross with Chief John Silva and members of the Stillaguamish Tribe, June 29, 1963

Photograph provided by the Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians.

When Esther got the news, she announced that the tribe would attack the convoy unless the Department of the Interior immediately granted them official recognition. She pointed out that her people had been petitioning the United States government for their rights for nearly 50 years. They had native membership and a formal tribal structure, and their representatives had signed the Point Elliot treaty. All they lacked was land, and that was hardly their fault. She was, she announced, seventy years old, and she was done waiting.

The train’s wagon master dithered. He recognized good theater when he saw it. On the one hand her threat had drummed up extensive media coverage, and he didn’t want to jeopardize an opportunity to spotlight the Bicentennial wagon train on national television. On the other hand, the Bicentennial Commission had orchestrated meetings with officials all along the route. If the tribe followed through on their threats and the train was delayed, it would generate a cascade of scheduling problems.

Government officials had more serious worries. The international press coverage was embarrassing. Worse yet, they weren’t sure whether the threatened “attack” was merely rhetoric or something more troublesome. At the beginning of the decade, the Kootenai tribe had closed down US Highway 2 for several days. Native groups blockaded Wounded Knee in South Dakota for 71 days, and they had taken over Alcatraz and Fort Lawton. The previous year, Judge George Boldt had ruled that treaty Indians in Washington State had the right to half of the local salmon harvest, a ruling that continued to generate angry protests from non-native fishermen. Might fishermen take this opportunity to organize another demonstration? Would Indian activists from other tribes become involved? Might things get out of hand, property be damaged, people get hurt?

Would Esther really stop the wagon train? And if she did, what would she do? They couldn’t be sure. They decided not to take a chance. On the day the wagon train was scheduled to arrive, a special assistant to the Secretary of the Department of the Interior was flown in to meet with Esther. “Why have you come?” she is reported to have snapped. “I did not send for you.”

He responded that the Department of the Interior was preparing a document granting the tribe official recognition, and that it would be ready in thirty days. Esther was unimpressed. He brought no documents with him, and she had heard such promises before. The show would go on.

Newspaper accounts say that when the wagon train arrived at Island Crossing, there were approximately 200 people, many of them Indians, standing in the road. As the wagon train passed in front of the little building, Esther’s son emerged. He walked in front of the TV cameras to the first wagon, grabbed the lead horse’s reins and informed the wagon master they weren’t moving until the Stillaguamish tribe received official government recognition. For several long moments, no one moved and nothing happened. Then, just as things got tense, Esther appeared. She wore native dress, walked slowly to the center of the road, and stood quietly until everyone was looking at her. Then she spoke.

For a tiny person, she had a big voice. She said that her ancestors had welcomed white men to this valley a century ago, and she was welcoming them now. She talked about the Bicentennial train and how it symbolized the strength and determination of the American people, but that for Indians it stood for a trail of tears, broken promises, ignored treaties, the loss of pride and dreams and the destruction of a way of life. “We stop this Bicentennial wagon train”, she said, “to bring to the attention of the nation that we have no other alternative, short of violence, to bring their plight to light and produce action.”

Then she did something surprising. She walked over to the wagon master, placed a good luck medallion around his neck, wished him a safe journey, and handed him a letter which she requested he deliver to the Secretary of the Interior. He promptly responded that the Stillaguamish tribe had the goodwill of the Bicentennial Commission, promised to deliver their message, got on his horse, and he and the wagons skedaddled down the road.

When 30 days, and then a year, had passed and the anticipated documents had still not arrived, Esther sent the Secretary of the Department of the Interior a frozen salmon. Attached was a cordial note saying she hoped he and his family would enjoy eating the delicious fish and reminding him that the Stillaguamish tribe had not forgotten his promises. It was said that the Secretary ignored the salmon, but that eventually the smell became so bad his staff had to dispose of it.

Maybe it was the salmon, maybe it was Bicentennial guilt, or maybe after 50 years, Esther had just worn them out, but finally in October 1976, the federal government granted recognition to the Stillaguamish. And in December of that year, at a dinner celebrating their victory, members of the now official American Indian tribe named her Chairman of the Stillaguamish.

Postscript: Esther Ross’ persistence helped obtain sovereign rights for one of the smallest tribes of Indians in America and brought it back from “near extinction”. Her efforts improved the quality of life for her people, and provided a precedent for other tribes.

How did she make it happen? Those who knew and worked with her say she did not hesitate to create her own rules, but at the same time she was not unjust or threatening. She had a great gift for creating dramatic moments. Perhaps her most effective weapon was her tenacity. In addition, she was born into a powerful family among the Coast Salish, a culture in which “rank and determination far outweigh gender in the course of life. Today, as in the past, both women and men routinely hold public responsibilities as equals.”

She did not choose an easy battle, and she and her family endured many hardships and stormy periods as a result of her all-consuming dedication. Like many others involved in the lawsuit, her intent was to affirm her Indian heritage and strengthen her native community. However, from the first, it was clear that some had other motives. Esther won many devoted supporters, but in the end, she also created some enemies.

When Esther died in 1988, David Getches, the attorney who worked closely with her on negotiations with the Department of the Interior and in the Boldt case, said in a letter to her son Frank, “When I think of Esther’s determination and strategy, I am not sure that the legal wrangling really made the difference in the successes finally earned by Esther and the tribe. From the poor people’s march on Washington, to stopping the Bicentennial wagon train, to the parades and news stories, to the prayers and friendships she fostered, it now seems clear to me that whatever happened right was because of Esther and not the lawyers and politicians and bureaucrats.”

Sources:

Ruby, Robert and Brown, John (2001). Esther Ross Stillaguamish Champion. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press.

Deloria, Vine (1977). Indians of the Pacific Northwest. Garden City, New York: Doubleday

Haeberlin, Hermann and Gunther, Erna (1930), The Indians of Puget Sound. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Bates, Dawn (1994) Lushootseed dictionary / Dawn Bates, Thom Hess, Vi Hilbert ; Seattle : University of Washington Press.

Cameron, David (2005) “The Native Americans,” Chapter 2 of Snohomish County / An Illustrated History, Index, WA: Kelcema Books

Thanks also to the Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians for their review and fact checking

© 2006 Ann Duecy Norman, All Rights Reserved