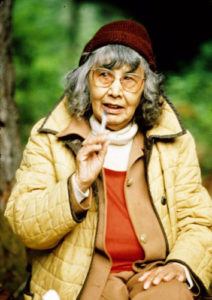

~ Elder of the Sauk-Suiattle Tribe

By Louise Lindgren

Jean Bedal Fish, elder of the Sauk-Suiattle Tribe, was dedicated to the preservation of her Native American culture. Her legacy included not only the recognition of her mother’s tribe, but its written history as well.

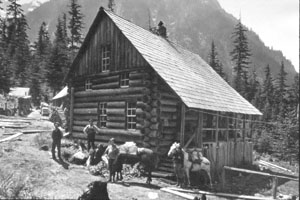

Jean was the daughter homesteader James Bedal and Susan Wa-wet-kin, only daughter of Sauk Chief John Wa-wet-kin. Born in 1907 in the cedar cabin Bedal built on his homestead, Fish entered a world dominated by towering trees, the Sauk river, and rain. The sounds of two languages entered her consciousness from the cradle. One language, English, could be written – the other, Lushootseed, remained only sounds, with no written record.

The Bedal children attended school on their own homestead southeast of Darrington and in Fish’s words, “eighteen miles from nowhere.” Learning to read and write in English was important, but after school she followed her mother’s instructions, given in the Sauk language and by example. Her father voiced no displeasure at the arrangement as long as his children kept up their English studies.

Jean Bedal’s first teacher was a lonely lady who found her surroundings highly disagreeable. She stayed only one term, but in that time made a lasting impression on the girl. When a sewing assignment, a doll’s dress, turned out badly, the angry teacher threw it in the fire. This prompted a strong parental protest and words that were a prophetic compliment, “Our Jeannie doesn’t need to be taught how to sew – she learns by observation!”

And observe she did – the changing of the seasons, the growth of forest plants and animals, the handling of her family’s horses, fishing, and the great shake bolt drives down the river. She observed her mother’s habits and housework, the cooking of fish on camping trips, and making fried bread. She observed her new and favorite teacher, a vibrant Dutch lass named Edith Froom, who taught by example and even instructed her students in the fine art of swimming in the river on the way home from school. And, she listened as the teacher read novels to her charges as a reward for work well done.

In 1916, life changed dramatically. James Bedal was stricken with a paralyzing stroke, ending his work as a shingle bolt producer. Survival was tough, and the family moved to the town of Darrington where the children enrolled in the much larger school there. Although their school had only “white” children, they at times had contact with Indian friends and relatives, staying overnight on special occasions.

One Christmas gathering was memorable for the drama that began at 3:00 a.m. A man rushed in shouting, “Pray, pray – the river is coming!” The Sauk river had become a raging torrent in full flood. For three days people listened to the deep earthshaking rumble of huge boulders under the water. Catholic prayers of her Sauk relatives were spoken in a language new to Jean – the Chelan dialect used by the traveling priests — more learning by observation for a young girl pacing the rain-sodden riverbank.

In a few years, another language was added to her mental storehouse. Her high school principal was a Catholic and tutored her in Latin, a language that Jean Bedal Fish could speak even in her elder years.

James Bedal’s illness eventually caused such hardship in the family that the young woman felt the need to stay and help on the original homestead two long hard winters. That put her behind one year for graduation and another year before she had the opportunity to go to college in Bellingham for a quarter of teacher training. Money for tuition came from her small savings earned doing work unusual for women of the time — working for the Forest Service, checking on hikers who passed the homestead on their way into a restricted logging area.

Even more unusual, both she and her sister Edith were excellent horse-packers and guides. Interviewed in her elder years, Jean Fish remembered, “I guess I was about six or seven years old. There was [my Dad’s] horse by the name of Pete, … a wonderful horse. So I used to sneak to the barn and had a hard time putting the saddle on – it was heavy. And then I tried to tighten the strap, and the horse would just blow his belly up every time. But I led him to a log to get on him and rode maybe a quarter mile and back again.”

At age 13, Jean led two attorneys into the mountains as a solo guide trip. A few years later she was lone packer on a 50 mile round trip to both White and Indian passes. That trip included dealing with a mean horse after spending the night at the pass and tracking down horses who had wandered off in the middle of the night. After delivering the family safely to the railway station in fading light, she returned to the homestead in the dark.

Another skill, also learned by observation and practice, was put to use for the rest of her life – cooking. She cooked for family, Forest Service workers, and beginning in 1929, guests at the hotel in Monte Cristo. In 1932, she married Russell Fish, son of the proprietor.

When the hotel closed in 1941 and her husband went off to war, she moved to Quinault and then Seattle, cooking for the Y.M.C.A., until an exploding gas range seriously injured her. After a slow recovery, she cooked for hundreds of war workers at Pier 90. When her husband returned from war they spent a number of years in Hoquiam, then returned to Monte Cristo to manage the lodge there before separating in 1956.

Two years of study at Edison Technical School in Seattle helped prepare Jean Fish for the important challenge that would follow. She had begun working with her sister, Edith, on the job of proving the enrollment and status of the Sauk Tribe, which never had been recognized by the U.S. government. For many years, they and others continued the work, and in 1972 Jean Fish finally stopped cooking in order to work even more on the tribe’s recognition. On September 17, 1975 the tribe received formal recognition as the “Sauk-Suiattle.” The dual name was not traditional, but was written in by a lawyer who connected the area of the nearby Suiattle River with the Sauk Indians. During the late ‘70s and ‘80s Fish worked for the tribe and served on the Tribal Council. From 1979 to 1983 she was Tribal Chairman, the equivalent position of being the President of the United States, and with a similar structure of government to administer.

Jean and her sister Edith then began the important work of writing their tribe’s un-written language and history. Jean finished Glimpses of the Past, which is now part of a larger work including the writings of both sisters, Two Voices: A History of the Sauk and Suiattle People and Sauk Country Experiences, edited by Astrida Blukis Onat.

From a dual-culture upbringing, through experiences of the wider world, to the homecoming of a tribe complete and recognized in a many-cultured country, Jean Bedal Fish saw and experienced it all.

Sources:

1. Interview with Jean Fish by Louise Lindgren, February 20, 1990

2. Jean Bedal Fish and Edith Bedal, with editorial assistance by Astrida R. Blukis Onat, Two Voices: A History of the Sauk and Suiattle People and Sauk Country Experiences, privately published for the Memorial Pow-Wow of June 9, 2000

See also the biographical article about James Bedal and Jean’s sister Edith in the Skagit River Journal of History & Folklore.

Revised and edited from a Third Age News (now Senior Source) Article published April 1991

© 2007 Louise Lindgren All Rights Reserved