by Betty Lou Gaeng

There are many wonderful stories of Snohomish County women who have led lives that have made a difference and inspired us in many ways. However, there were others who were little noted. They were the women native to this area. They were born here before the white men came—before the treaties. Even though little is recorded about them, their fight for survival, their successes and failures led the way for the women who followed. One of these native women was Lillie Hayes Radley.

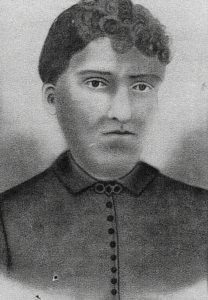

Lillie was born, as she would say, a long time ago. She was a full blood Indian woman living during a time when it was not easy being female or Indian. Lillie’s story is not a happy fairy tale. Her prince charming turned out to be neither princely, nor charming. She was a victim of the time, and her life ended much too soon.

Lillie never became famous. She never learned to read or write. She never had the chance to become active in a community. Most of the time, she was just known as Lillie or Lilly, and it was a battle just to survive. She had no rights, and no one to protect her. Circumstances forced her to eventually turn the care of her daughter over to others. She hardly knew her grandchildren, and never knew that she had great grandchildren. Lillie would be surprised to learn she has a great-great-granddaughter who respects her, and wanted to learn more about her great-great-grandmother. Because of this caring descendant, some of Lillie’s story has unfolded.

The young native women of today have many opportunities. They can go to school, and on to college. They can have careers—they have many choices. Lillie had none of these advantages. Even so, Lillie and many other native women influenced the early development of Snohomish County. They were often used, abandoned, and little is known of them. However, they are part of this county’s history.

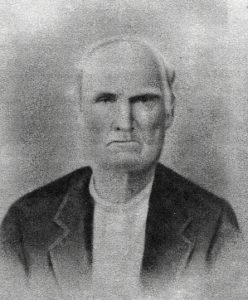

James Hayes

James Hayes

There is no record of Lillie’s life before the 1860s. Census records indicate she may have been born about 1843. She had a sister, but what had become of their parents is unknown. Like so many of the young native woman in the Puget Sound area during the early 1860s, when the white men began arriving to work in the woods, Lillie met and married one of them. His name was James Hayes and he came from a culture foreign to Lillie. In fact, he came from the other side of the country—New York City.

Many of these men coming to this primitive forested land took Indian wives, either by legal marriage, according to native ways, or by cohabiting. Most came from the well-settled areas of the East Coast and some from England and Scotland. They had no knowledge of survival in this wilderness land. Much of that survival was taught to them by their Indian wives. These ladies knew the ways of living off the land, and how harsh and unforgiving the damp and cold winters could be. They had been taught to be hard working, knowledgeable of the environment, and obedient. Some of these marriages survived and others did not. Some of the native women adjusted to the foreign ways, were respected by their husbands, and became active in the developing communities. They taught their children the ways of living in a different cultural environment, enabling the generations that followed to take part in the building of communities.

Lillie and James were legally married according to Washington Territory’s 1866 law. Lillie’s name appears as Caroline Lily on the marriage certificate. Lillie and James Hayes were married by a justice of the peace at James’ home in Monroe, Snohomish County, Washington Territory on May 14, 1867, with John Elwell and Charles Harriman as witnesses. At the same time, these two witnesses, friends of James, also married young Indian women. John Elwell married Sarah Smith and Charles Harriman married Elizabeth Pero. The Harrimans and Elwells had solid, long-lasting marriages. This was not to be for Lillie and James Hayes.

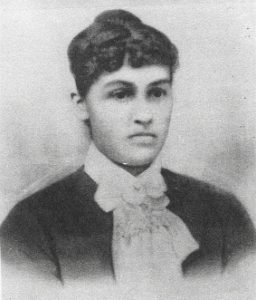

A daughter, Catherine Hayes who was known as Katie and sometimes Carrie, had been born to Lillie and James in 1863. Throughout most of the years of this marriage, James Hayes did not provide for the care of his wife and daughter. They lived near Monroe and then in Snohomish City near the homestead of John Harvey and his family.

In April of 1879, Lillie divorced James Hayes citing his abandonment of both her and their daughter, and also his addiction to drinking. In the divorce papers, Lillie stated “I have one child Katie Hays…she is at John Harvey’s across the river, she has been there for a long time.” Lillie asked the court to allow that John Harvey be the guardian of daughter Katie. The divorce was granted on April 22, 1879, and it was ordered and adjudged that Katie Hayes, the child of James and Lillie Hayes, be left in the custody of Mr. and Mrs. Harvey. Carrie Hayes Tilton

Lillie went to live near the Jimmicums/Chimicums south of Monroe, where she labored at field work. About 1881, Lillie married for a second time. This time she made a better choice. She married Englishman Joseph Radley.

Lillie and Joseph’s marriage was to be a short one. Lillie had a long illness and died Friday, October 9, 1885 at approximately 40 years of age. Joseph Radley cared for his wife with the help of friend and neighbor Mrs. George Allen. After Lillie’s death he wrote to daughter Katie. Katie (now called Carrie) was married to Oliver Tilton, and living in Clearbrook, Whatcom County.

Lillie’s son-in-law Oliver Tilton surrounded by Lillie’s surviving grandchildren and great grandchildren. This photo was taken about 1912 or 1913, and shows Oliver Tilton with his and Catherine/Carrie’s children still living at the time. Betty Muzzall’s grandmother is the one in the back row on the right–Stella Tilton Swanson. Lillie Hayes Radley is buried at Priest Point Cemetery on the Tulalip Indian Reservation, near her sister who had died seven months before Lillie’s death. However, no grave markers have been found for them. Joseph Radley went back to living alone and died in 1889 at the age of 38. He is buried at Mukilteo Cemetery—a headstone marks his grave.

Lillie’s daughter Catherine/Carrie Hayes Tilton died from a bout of measles in May of 1898 at the age of 34. She is buried at Clearbrook Cemetery next to her husband Oliver. Through this daughter, Lillie has a long list of descendants.

James Hayes never married again. In spite of his admitted love for whiskey, James lived a long time, dying in Monroe in 1920 at the advanced age of 95. James Hayes is buried at the Monroe Memorial Cemetery.

If Lillie were around today, she would no doubt be proud of her large family, and especially the great-great-granddaughter who wanted to know more about Lillie and her life. Also, Lillie would assuredly be pleased at the advancements made by other native women. Lillie didn’t have the chance, but she helped in leading the way.

Sources:

Family photos, letters, and documents provided by Betty Muzzal, gr-gr-granddaughter of Lillie Hayes Radley. These have been used with her permission.

Washington Territorial and State census records.

U. S. Federal Census Records.

Information from the Washington Digital Archives < http://www.digitalarchives.wa.gov >

Cemetery information from < http://www.findagrave.com >

Article from the Everett Daily Herald, March 1, 1913.

© 2010 Betty Lou Gaeng, All Rights Reserved; WLP Story # 65